We recently visited the Protestant Cemetery in St. John’s, NL, to take a look at the condition of the site in general, and get an idea of where work needs to be potentially done in the future. It’s still fairly winter-like here in Newfoundland, so Ian and I joked that we should have brought our snowshoes for the walk. We did actually see snowshoe tracks at the cemetery as well, so someone had the right idea of how to avoid sinking and dribbling coffee all over themselves.

Among the amazing sculptural work and beautifully simple stones, we noticed a number of repairs that were less than ideal. We do want to stress that most of the time repairs are carried out using techniques that were, at one point, thought to be the best option. Conservation, like any field, changes and adapts as new information arises, and many older techniques for gravestone repair such as using iron and concrete, are now known to cause long-term damage to historic stonework and should be avoided. If you are interested in cleaning or repairing a gravestone, please read up, get permission, and when in doubt consult an expert. That is what we’re here for!

Metal Bracing

A classic repair job that we definitely do not recommend, you often see historic gravestones braced with strips of iron that are bolted directly into the stone. This causes damage to the stones in two ways: firstly, in order to secure the strips of metal, bolts are drilled through the soft stone, taking away material which cannot be replaced. Once the bolts and metal braces are secured, rust creates another problem by expanding in and against the stone, cracking the surface and allowing water to seep inside.

As you can see in the photos below, these two gravestones, marble (left) and sandstone (right) have been repaired with an unknown adhesive and metal braces. Curiously, the stone on the right appears to have both a rusted iron brace and two metal rails or drawer tracks, which have been powder-coated but are rusting on the end. We’ve never seen anything like that used on a gravestone, and do not recommend using any kind of metal around historic stonework for repairs, if it can be avoided!

The back of this gravestone has three rusty iron bars, bolted to the stone

This gravestone was repaired with an iron bar and what appears to be drawer tracks

Painting a Gravestone

A common thing to see on Newfoundland gravestones, the stone pictured below has been covered with paint. While it seems like a good idea, and for a time the paint may make the letters a little more easily read, paint is actually quite bad for gravestones. Especially when the stones are soft, like limestone, marble, or sandstone, paint traps moisture within the stone itself, causing it to weaken and become more susceptible to cracking and breaking. Paint will also cause the surface of the stone to weather away more quickly than it would if it were left to the elements. Notice how, in the closeup image on the right, the surface of the stone is pockmarked and weathered.

It is difficult to remove paint. If a paint is water-based, using something like D/2 and/or water and a soft brush will help remove some of the paint, but this also risks scrubbing some of the weathering stone away as well. If a paint is oil-based, things would be even more complicated. Never use a paint stripper, sand blaster, or pressure washer to try and clean a gravestone however, as this will strip the hard surface of the stone away. How to best preserve the stone? Try recording it with photographs and drawing the imagery and inscription in a notebook or onto a crowd-sourced app like BillionGraves or FindAGrave.

Small stone obelisk, painted grey

Close-up of weathered stone

Rubbings & Scraping

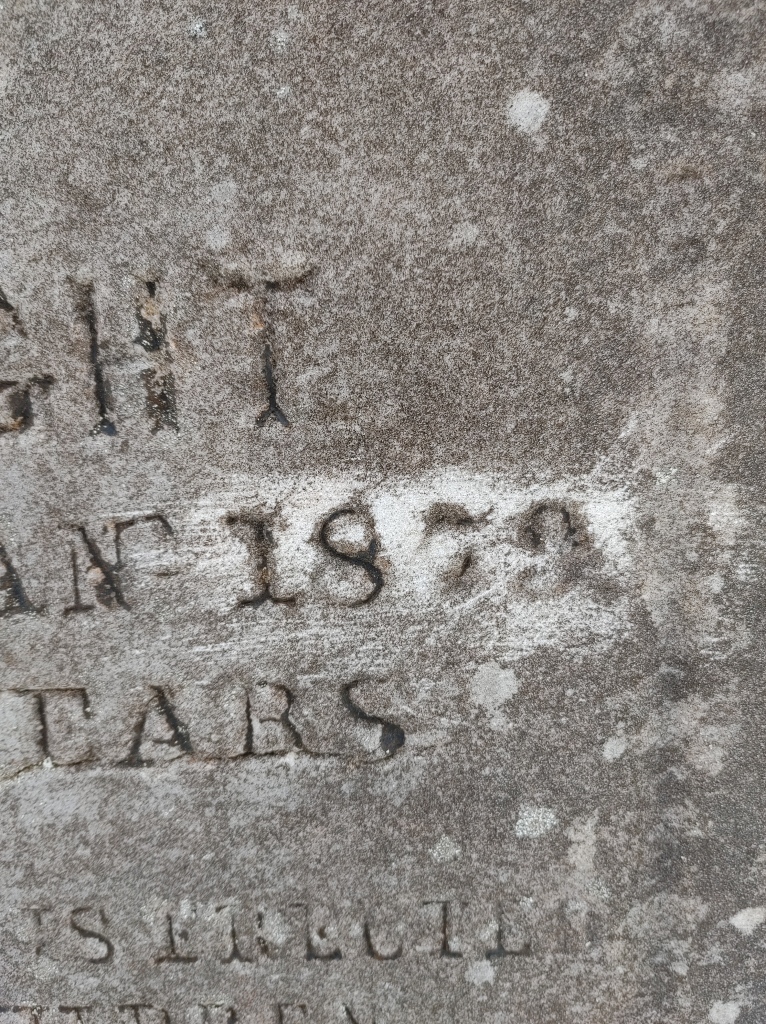

Below, we see the gravestone of Thomas and Ann Knight. The stone is relatively well preserved, with a lovely iron railing around the plot and only minor lichen growth over the surface of the stone. It appears that someone has attempted to paint the lettering in the past, but perhaps more worrisome are the white scratch marks over the dates. This is a clear indicator of an individual either taking a rubbing of the dates onto a piece of paper with a tough writing implement, rubbing hard enough to cause that damage, or by someone scraping at the stone itself in an effort to make the dates more visible.

We do not suggest that anyone take gravestone rubbings. This is an example of a recording technique that used to be common, until we realized just how much damage it was actually doing to the graves. When you rub the weathered stone, even with a crayon or pencil, small pieces of the stone will be dislodged. The more people do this, the more damage is done over time, until the face of the gravestone becomes unreadable. There is also the risk of breaking the gravestone, if it is thin and made of a soft stone, from the pressure of pressing against it. They may seem invincible, but gravestones need care to last.

If this damage was caused by scratching lichen or other substances from the surface of the stone itself, there is not much we can say other than to strongly advise against doing that. It is removing physical pieces of the gravestone’s surface, making the letters and numbers even more difficult to see in the future.

Thomas and Ann Knight’s grave marker

Close-up of date ‘1879’

Close-up of date ‘1882’

Thanks so much for reading, and we hope you found some useful information in this post. As we creep closer to spring, we are looking forward to the start of our field season and sharing our work with you all!